Sir Alastair Pilkington

Sir Alastair Pilkington

Born in 1920, Alastair Pilkington was educated at Sherborne School and Trinity College, Cambridge. He became an officer in the Royal Artillery just before the outbreak of World War II, and later fought in the Mediterranean, where he was taken prisoner after the fall of Crete. When the war ended, he returned to Cambridge and gained a degree in mechanical science. He joined what was then Pilkington Brothers (there was no family connection) as a technical officer in 1947.

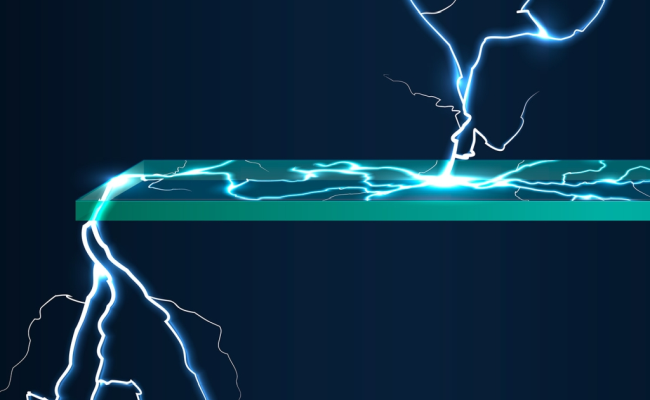

When he started work on his process, the target was to make, more economically, the high-quality glass essential for shop windows, cars, mirrors and other applications where distortion free glass was necessary. At that time this quality of glass could only be made by the costly and wasteful plate process, of which Pilkington Brothers had also been the innovator. Because there was glass-to-roller contact, surfaces were marked. They had to be ground and polished to produce the parallel surfaces which bring optical perfection in the finished product.

In the process, a continuous ribbon of glass moves out of the melting furnace and floats along the surface of a bath of molten tin. The ribbon is held at a high enough temperature over a long enough time for the irregularities to melt and for the surfaces to become flat and parallel: because the surface of the molten tin is flat, the glass also becomes flat. The ribbon is then cooled down while still on the molten tin, until the surfaces are hard enough for it to be taken out of the bath without rollers marking the bottom surface: so a glass of uniform thickness and with bright, fire-polished surfaces is produced without the need for grinding and polishing.

Alastair Pilkington encountered numerous setbacks during his seven years of hard labour. People, he recalls, kept asking him: 'When will you succeed?' All he could say was: 'We will know the answer to that only when we have succeeded.' The cost was far higher than anyone had bargained for, and it took considerable courage for the board of directors to go on supporting him. When he finally made it, they decided to license the process, chiefly to get some income but also in order to ensure that others would not find it worthwhile to research their own technology.

The first foreign licence went to the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company in 1962, and this was quickly followed by manufacturers in Europe, Japan, Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union and others in the USA. Today, around 260 float plants are in operation, under construction or planned worldwide. Pilkington operates 25 plants, and has an interest in a further nine.

Sir Alastair Pilkington died in 1995.